Many people avoid learning from adoptees because adoption is considered a touchy subject. You are not weak or broken because you were adopted. On the contrary, it can make you stronger. Adoptees are often treated as though their adoption defines them, but it isn’t the reason behind everything adoptees do or think. Despite its complexity, this is a topic that many people poorly understand.

Sharing adoption stories is a personal choice, and each person has a different comfort level. It does not make them fragile in any way! You can decide whether or not to share your story. When I’m asked about my adoption, it’s easy to sense discomfort, but I applaud those brave enough to ask. Everyone interested in the topic should feel free to ask and should not take it personally if someone doesn’t wish to share their experience.

The story and perspective I share do not represent all adoptees. Each story is unique. Adoption has become a sensitive subject in recent years. My adoption story has always filled me with pride, and I have always admired my adoptive parents. I have always believed that I was adopted into a loving, Christ-centered family marked by grace.

There can be noble reasons for wanting to adopt, perhaps even a calling. An individual’s decision to become a parent is very personal, and the reasons for adopting differ from family to family. Some people cannot conceive, while others desire to expand their family.

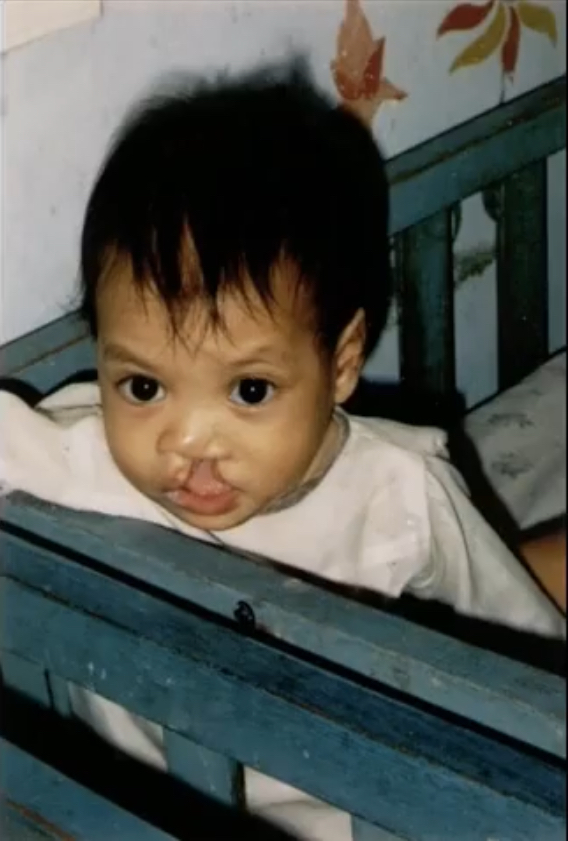

I grew up in a small village outside of Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Due to having a cleft lip and palate at birth, my biological mother surrendered me for adoption. She cycled ninety miles with her sister to get to the orphanage in Phnom Penh.

My journey of adoption began after spending roughly two years in the orphanage. My future adoptive parents decided to find a child closest in age to their youngest biological daughter. Creating artificial twins, or virtual twins, occurs when two non-biological siblings are within eight months of each other. This often happens when a child is adopted close in age to one already at home or when two nonrelated kids are adopted simultaneously. Recently, many countries have prohibited families from adopting nonrelated children simultaneously, and adoption agencies discourage virtual twinning. The idea is that each child should have their own “spot” in the family, and having significant distance between siblings makes this easier. Additionally, this speaks to the importance of birth order, which is why adoption professionals recommend families add new children in the same order as their originals. My adoptive parents arbitrarily chose my birthday to be after their youngest biological daughter. The consequences of this unknowingly affected my future.

Each year, around my birthday, my adoptive parents talked extensively about how they adopted me and why they chose me. My adoptive father told me that the agency would send photos of each eligible orphan. “Seeing your baby photo in the pictures, we knew we could not live without you. It was always our dream to find someone close to our youngest daughter’s age.” I have held on to this story for years. However, as I grew older, my adoptive parents increasingly insisted that I was their youngest daughter’s companion. We were introduced as artificial twins with excessive pride by my adoptive parents. In any sibling dynamic, comparisons arise, but they are heightened when artificial twins are involved. Our unique relationship resulted from our identifying as twins despite not being paternal twins. Considering our birthdays were twenty-one days apart, my adoptive parents decided we should combine our birthdays to keep things fair. Since my adoptive sister’s birthday fell before mine, we always combined them. Initially, we were both satisfied with the arrangement and delighted to tell others that we were born on the same day. As I grew older, my desire to share my birthday diminished because I knew that celebrating with my adoptive sister would require minimal effort. We also shared our friends, making playdates and sleepovers impossible without each other.

At sixteen, we both obtained our driver’s licenses, triggering comparisons between us. Eventually, the rules of friendship relaxed, and we often hung out on our own. This generated more division as our friends favored one of us over the other. Over time, we gradually drifted apart.

In high school, the concept of equal opportunity started to erode. Our individualities bloomed, and we became increasingly competitive. By exploring my beliefs, I challenged my adoptive parents, causing them to disengage from me. Their attention and admiration focused on their youngest biological daughter, leaving me feeling unimportant. My opposition to my adoptive parents’ beliefs led my adoptive sister to emulate them. My perceived disloyalty led her to prioritize herself in the family, which I viewed as selfish.

When my adoptive parents began the adoption process, they believed their hearts were in the right place (and they still do). However, their tendency to favor their youngest biological child overrode this as their human nature prevailed. Despite our best intentions, all humans have flaws that can derail even the most honest and upright people. My adoptive parents ignore their human fallibility by believing that if you’re saved, you have been made sinless. They pushed me out of their lives to reconcile the repression of their human fallibility.

An adopted child can feel lonely in a way that is unlike any other experience. As an adoptee, I constantly had to defend my views on adoption. Often, I felt compelled to choose between being happy or sad. The people around me made me feel that my emotions could not vary. There could be no gray area; it had to be black or white. To process my mixed emotions, I desperately needed that gray area and validation that feeling multiple emotions at once was okay. People can be happy and hurt, thankful and angry, or loved and lonely. After my adoptive parents were physically and emotionally disengaged from me, I developed feelings of loneliness. Fear of upsetting them made it difficult for me to express any hurt or love I felt. Although unintentional, this withholding of emotion created a sense of isolation. My adoption truths were often deemed invalid by my adoptive parents, and it was a vicious cycle I could not escape.

I realized that my adoptive parents view relationships with their children as transactional. To receive love and support, you have to do things for them. By adopting, my adoptive parents thought they were heroes swooping in to save the day. Those with a savior complex, like my adoptive parents, believe their charitable deeds will bring them love and acceptance. When adopting a child, a savior complex attempts to rescue them from difficult situations. Children don’t need to be rescued or saved; they need a parent’s unconditional, tenacious love. My life in my adoptive parents’ world left me feeling suffocated, and my escape has enabled me to flourish in ways I never thought possible.

Through therapy, messy conversations, and tears, I have owned my adoption narrative. Remember, there are GOOD people who choose to adopt for the right reasons. The problem with my adoptive parents is that they had ulterior motives, so we both lost. Their biological daughter struggles to have her own life because she’s trying so hard to please them. I have my own life and am thriving, but I have lost my family in the process and have faced the brunt of their shame and anger.

Leave a Reply to Cyndi Peck Cancel reply